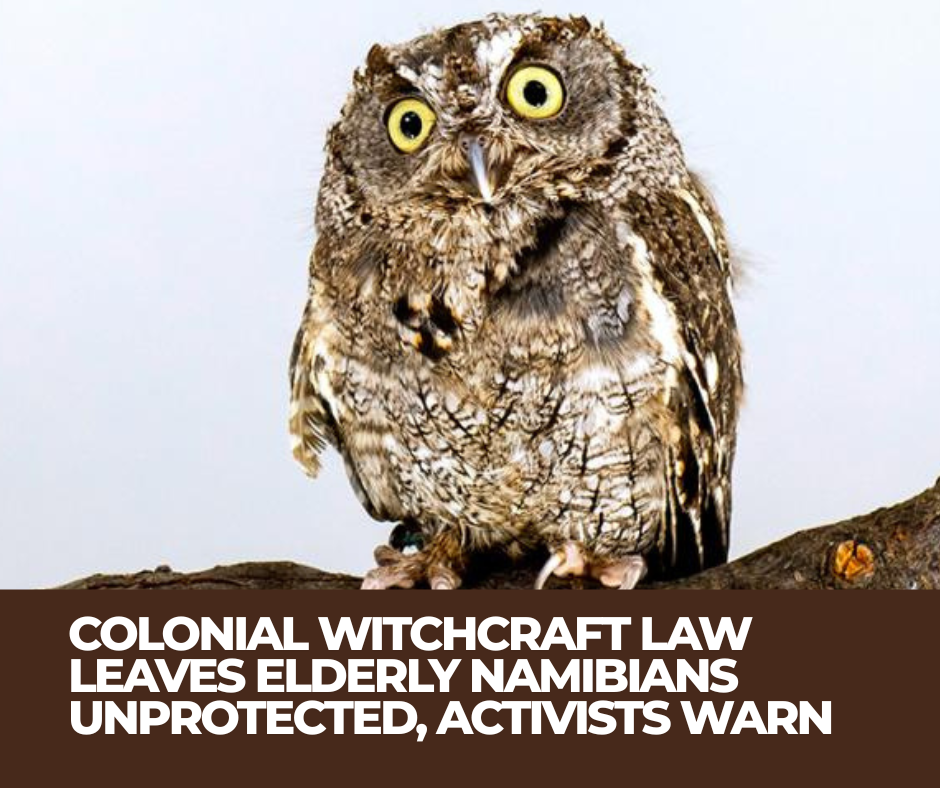

Namibia’s outdated witchcraft law is under scrutiny as calls grow for urgent reforms to better protect vulnerable groups from abuse and exploitation.

A proposal submitted to the Ministry of Justice in May calls for the repeal of the Witchcraft Suppression Proclamation of 1933. Critics argue the law is ineffective in preventing the abuse of elderly people, persons with disabilities, and individuals suffering from dementia, who are often accused of witchcraft.

For two decades, a woman from Omuramba village in the Kunene region was kept in isolation by her family, who believed she was a witch possessed by evil spirits.It was later discovered that she was actually suffering from dementia. Berrie Holtzhausen, founder of Alzheimer’s Dementia Namibia (ADN), found her in 2012 and helped free her from confinement.Holtzhausen explained that the family had misunderstood her condition, wrongly assuming she posed a danger to others.

Human rights organisations, including Alzheimer Dementia Namibia (ADN), warn that witchcraft accusations have become tools of violence and financial gain. ADN has reported cases where neurological conditions were mistaken for witchcraft, leading to heavy fines and punishments from traditional courts.

Namibia is bound by international human rights agreements such as the UN Human Rights Council Resolution 47/8 and Pan-African Parliament guidelines, which call for states to criminalise harmful practices linked to witchcraft accusations and ritual attacks.

The Witchcraft Suppression Proclamation of 1933 makes it a crime to:

- Accuse others of using supernatural powers to cause harm.

- Force others to make witchcraft accusations.

- Claim to practice witchcraft or related supernatural activities.

Violators face up to five years in prison, a fine, or both.

However, the law has rarely, if ever, been enforced in practice since Namibia’s independence, with no convictions recorded under it.

Concerns also remain about some traditional and religious healers accused of exploiting belief systems for financial gain by offering costly “cleansing” services.

Although lawmakers have acknowledged the need for reforms, enforcing change remains difficult due to the deep-rooted belief in witchcraft within many communities.

The Ministry of Justice has yet to respond to the proposal, but campaigners are urging Parliament to prioritise the issue, stressing its impact on human rights, health, and community safety.